Click an image to read their stories.

Charee Stewart, RN

Interviewed 09.01.20

Over and over while I was creating my Frontline Caregivers project, doctors told me I should be talking to nurses, that they’re the front of the front line. Charee Stewart is a nurse coordinator for the County of Riverside. She’s been a registered nurse for nearly 14 years. Prior to that she worked in healthcare for over 10 years. “It’s the only career I’ve ever had.” If I were ever to be critically ill, hers is the face I would hope to see.

A consistent observation among disciplines is how COVID-19 has forced us to change how we communicate. Healthcare workers experience sensitive encounters daily. To connect and express empathy is paramount to the best experience and outcome for the patient. But to protect everyone, the wearing of face masks as a society is imperative. The trade off now is sometimes the inability to interpret facial expressions, which are the foundation of how we convey feelings and understand interactions with others.

As a nurse, you want to protect everyone. The trickle-down effect from that now is you are trying to protect everyone, but you are also taking away an important piece of the patient’s treatment as well. One-on-one encounters and physical touch are limited in certain instances. It has been exceedingly difficult and challenging, especially in a critical care situation. Research has shown that patients who have the misfortune of being in that environment, experience better outcomes when person to person touch and family support is factored. These are just as important as any medicine we can offer. For instance, the intubated patient is sedated, but can still maintain a level of consciousness. the patient’s sedation level is enough to keep them comfortable, since there is a foreign object in the airway, we are relaxing muscles to prevent gagging or choking. But there is still ability to follow commands in many instances. As part of the neurological exam the patient may be asked to; wiggle toes; squeeze hands etc. Also, intubated patients must demonstrate ability to follow commands before extubation can occur. There is a trial of the patient self-supporting their breathing; ability to sit upright; and follow commands etc. Additionally, during end of life scenarios, sense of hearing may be the last of the five senses to go. The voice and warmth of a loved one is a great source of comfort and much needed during those times.

In terms of visitation, COVID-19 is a highly contagious disease with the ability to spread rapidly and lead to deadly outcomes. A person can have COVID-19 with zero to very mild symptoms and unknowingly spread it to others. Critically ill patients with chronic medical conditions are the most vulnerable and a large percentage of those presenting to us for care. Many facilities have restricted visitation to virtual meetings, phone or video in many instances. But we also know the support of patients’ family is equally important. To hear their voices and be physically comforted is a vital piece to patient’s care and outcomes. Research shows that patients experience better outcomes when touch and family support is factored. They’re just as important as any medicine we can offer.

So loss of connection has really affected healthcare for us all on an emotional level as well.

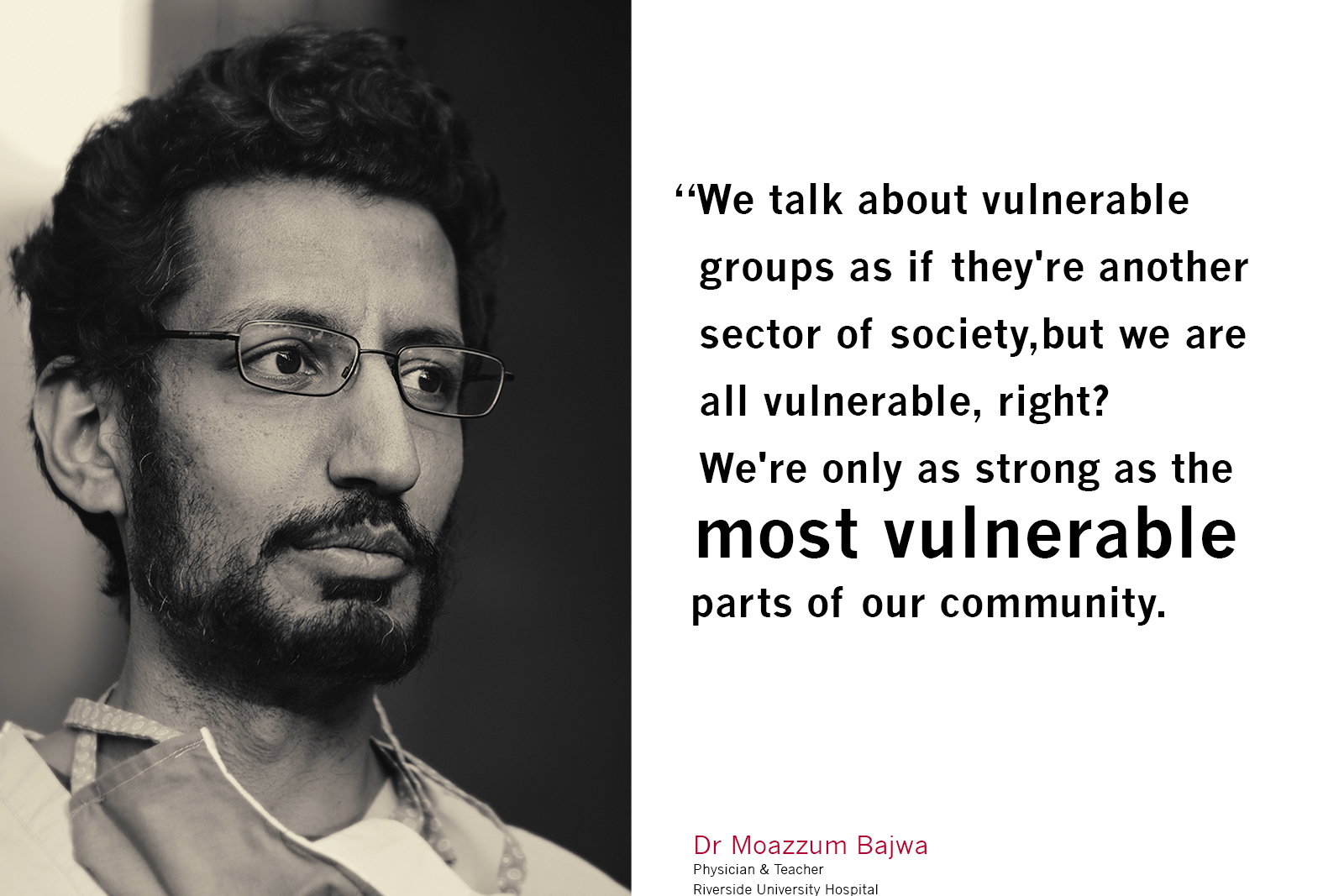

Dr. Moazzum Bajwa

Interviewed 07.01.20

My name is Moazzum Bajwa, and I’m a family physician in Riverside, California. I did my training and currently practice at Riverside University Health Systems (RUHS) in Moreno Valley, California, the county hospital for Riverside County. It covers a huge area of mostly underserved, vulnerable populations from the entire span of Riverside County, which runs from the Eastern edge of Orange County, all the way to the border of Arizona. It’s a huge, huge area that we serve, and by virtue of that, our patients come from a number of backgrounds. They’re usually very high acuity in terms of their medical conditions, and don’t often have access to strong primary care, which is the focus of my work outside of the hospital. I spend a lot of my time in the clinic settings, trying to build up our public health and primary care infrastructure around Riverside County.

In the experience of our hospital, there’s been a huge change in the last three months, of not doing elective surgeries, and of only having patients come in to the ER with certain scenarios, and separating them out that way, and even in our hospital based service. So every few weeks I’ll be the supervising physician on our teaching service, which usually holds anywhere from 15 to 20 patients a day, and the residents are the ones who are running the show. But ever since COVID has happened, we’ve limited the interactions with our residents and patients who are suspected of COVID. So they take care of patients who are coming in for non-COVID related issues; complications from diabetes, heart attacks, infections, what have you, and then myself as a supervising physician, will go see all the COVID patients separately. After I’ve seen that initial group of patients on my own, to limit additional exposure to our residents and our trainees and our students to COVID patients unnecessarily. But by virtue of that, they lose a huge part of their educational exposure and ability to know what it’s like caring for those patients and understanding the nuances of these respiratory illnesses.

Prior to COVID, students and residents typically would’ve had the most contact time with our patients, developing the ability to interact with patients and really get to know them, spend time with them and developing a bond of trust. But when they don’t have that, and they’re just putting in orders through a computer and not able to actually see the patients, having to rely only on what I tell them, it’s very different to the level of therapeutic bond they would have experienced previously. So that’s been a challenge for all of us as we’ve adapted to it. But I will say that at least in Riverside County at the onset of the pandemic there, the public health response and leadership was fantastic. And they did a really good job of anticipating the needs in terms of PPE, and of how to support the physicians in these situations, and how to put the public health at the forefront. I believe Riverside County was the first or second county in the state to require masks when people left home, and to put certain restrictions on distancing and public engagement. So at least at the onset, and it may not be reflected right now, but at the very beginning, that public health response was excellent and I was really proud to be working in a system that reflected those values.

But despite how happy and inspired I was by that really excellent response in the beginning, unfortunately Riverside County was also perhaps the first to bow to external and political pressure to rescind a lot of those restrictions. And so it was a little bit before Memorial Day that they kind of took the gas off the pedal and started to ignore, or selectively respond to those public health directives and say, “Well, that’s fine, that’s all well and good, but we’re going to change things up and try to do the things that we want to do and allow these businesses to reopen”. And only now are we starting to see the clinical ramifications of that as we hit the expected surge that was going to come along, and everyone’s kind of throwing their hands up, “”How could we have prevented this?” And it’s so clear, if you just kept doing what you’d been doing at the onset, we could have spread this out a little bit more, but we decided not to do that. And here we are.

Working with primarily students, trainees and residents, there’s always a sense of anxiety. But even pre COVID, there was a strong sense of camaraderie, that we’re all part of a team and we’re doing this together. And even as faculty, we have a goal that we’re training the future generation of physicians in a model of better than how we were trained, and a better version of what we want the healthcare system to look like. And when you lose that direct contact and teaching ability, whether it means residents are doing phone visits, so you’re not seeing them face to face, or you don’t have an opportunity to give them feedback directly, a lot of what brought us to this profession as teachers is lost. You don’t get that same gratification or that sense of comradery, that yes, we’re all doing this for the betterment of our future physicians. And it becomes very, very myopic.

A question we all ask ourselves as physicians is how can I just mitigate the damage right here and right now to these patients? And that engenders a lot of anxiety, it makes you feel inadequate in the face of a pandemic. No matter how good your clinical skills are, you may not be able to help these particular patients. And I think that’s compounded by just the abject isolation that these patients with COVID are dealing with. I mean, in the times when I was covering the COVID units, I did it in April and I’ll be doing it again next week, when I would go into the rooms to see these patients who are isolated on COVID, it might be that just myself and the nurse are the only human contact a patient will have for 24 hour periods. And it’s such a different and harrowing level of isolation that you really can’t fathom. They patients are overjoyed to have human contact, but you can also see desperation in their eyes, of praying for some good news that you frankly may not have for them. And they’re just waiting for some updates, waiting for some information. And I may talk on the phone with them later on, or video chat, but it’s not the same thing. And as a physician that weighs on you so heavily because like it or not, and I have my own personal thoughts on this, we ascribe so much of our identity to our role as physicians.

It’s a dangerous game because when things go badly, as they inevitably do sometimes, we take that very, very personally. And, you see that. You talk to any physician about the idea of burnout or how this impacts their wellness, and this is a well-stated thing; how much this can impact your resiliency and how quickly you can bounce back. I can say unequivocally the most down and depressed I’ve felt as a clinician was during that first week when I was taking care of those COVID patients in the hospital. Not because the work was so demanding or because I was doing so many crazy things, but really just because I was feeling very isolated and seeing how lonely those patients were made me feel like there was nothing I could do to fix that situation. And I felt a ton of despair.

I think the challenge that I faced was, as I started to zoom out more and more on the wider perspective that this pandemic has brought to us, I would get really depressed about how inadequate my work was, or how there wasn’t really anything I could do to fix this overall problem. And that I, as a physician, my reach is limited. And as a society, it brought up so many concerns and so many issues that I think are now being amplified by even more things in terms of the black lives matters protests or other societal movements that are showing just the number of inequalities that exist in our system. And as I zoomed out more and more, it just became overwhelming. And I would have periods of deep sorrow related to that.

But what I realized was the more that I could actually focus in on my little world, and the community in which I exist and the work I’m passionate about, I felt much more hopeful and confident about what we could do. And then seeing the beautiful community response that came out in so many ways to the initial onset of the pandemic, and even now with black lives matter, just watching how my neighborhood and my community has responded in positive ways. And though that may not get the publicity that some of the negative stuff of the protest do, it’s allowed me to re-center and say, “Okay, well, here’s what I can control, here’s what I can do. And this is my impact”, instead of focusing on all the things that I can’t control. But it was really hard at the start. That sense of unease and dread continues to simmer underneath the surface, perhaps always, but I actively try to engage my mind in what I can focus on, right here and now. Not by being blind to what’s going on and what’s going to happen, but, for example, as an educator, dealing with curriculum and several hundred students, I have to say, okay, if these hundred students can’t go to the clinical site, it may be open right now, but if we anticipate that by end of July, it’s going to be just like it was in March and April, where they can’t go to these sites, what are we going to do? How are we going to supplement their education, their curriculum, and keep them on track for their progress as future physicians.

So that’s the more obvious and stated part of it, just adapting to changes that lots of professions are going through. But from a public health standpoint, my undergraduate and master’s degrees are in public health, and I worked in that setting for a while because that’s my first love, medicine for me is the action arm of the public health world, which is why I’m a primary care physician. My academic work is focused primarily in community health, social medicine, and health equity. Highlighting and identifying research around health disparities. And this pandemic has highlighted gaps in our healthcare system, as to who can afford care, who can pay for care, which vulnerable populations are at the highest risk of the worst outcomes from the pandemic.

And these are all issues that we’ve collectively failed to address as a society, and now they’re coming at us full speed. And we tend to take a very reactive approach where, if this thing comes up, we’ll just address it then. And that’s not the way a good functioning health care or public health system works. Most of the other countries in the world that do have a strong, robust public health infrastructure have responded very well to the pandemic and aren’t seeing such horrible outcomes, but unfortunately, that’s how our healthcare system is set up. You know, one of the common themes that I hear from my non-medical friends is about how the healthcare system is broken. The healthcare system is not broken. It works exactly as it’s intended as a reflection of our values as a society, it works to selectively choose who can get the right kind of care and who can’t, and it ties your livelihood and your job to your ability to obtain health care, which is so immoral and so wrong.

But everybody is so complicitly okay with it and we don’t actually use our voice and our votes to make a difference. And so all of us are indicted in what we’re facing right now. And it’s so easy to get caught up in the political weeds of “Oh, I don’t need to wear a mask, this is my liberty”. That’s all just smoke and mirrors. Fundamentally, what matters is, how do we value human lives? And what steps are we going to take to actually show that that’s what we care about? And that’s what I said about kind of zooming out. If I zoom out too far, I get very dismayed about the prospect of how Americans respond to these sorts of things.

You know, if you look historically, there was similar if not more fervent pushback against seatbelts when they came out as a method of safety. People were like, “No way, this is taking away my liberty. I’m not going to wear a seat belt, this is ridiculous, it’s overreach by the government.” And now it’s the most second nature thing in the world. But, I don’t know if it’s a selfishness or just not thinking about others, but when I drive around on the highways, I look around and I would say at least 80% of people are texting and driving. And if you ask somebody one-on-one if they text and drive, they’ll say, “Oh no, of course not.” If you say do you realize that you’re going to kill somebody if you do that, it just doesn’t register. I think we’re seeing that manifest in some ways with this mask issue. People say, “I don’t really need to wear the mask because it’s not affecting me, it’s not going to happen to me.” Until it does. Until your grandparent falls ill. And these conversations are going to keep happening for months and months, and people are going to find political ways to resist any recommendations for the greater good. So all I can do is focus on those vulnerable populations that are my passion and say, “Okay, well, what can I do to at least mitigate damage here? And how can I best support these groups that are going to get the worst outcomes from this pandemic?”

One of the hardest realizations, I think even from medical folks, is that at the onset of the pandemic, ‘social distancing’ were kind of the words that we used to say, “Okay, here’s how we fight this”. But people don’t realize that social distancing is a privilege and it’s a privilege that isn’t afforded all of my patients in the clinic. The ones without disposable income who can’t stockpile groceries for a month, the ones who depend on group meetings to maintain sobriety, the kids who are missing out on behavioral or speech therapy, because they have special needs, so many subsets like migrants and refugees who won’t even access the healthcare system for fear of the ‘Public Charge’ rule. Which is a very calculated campaign by the federal government to scare anybody who is in the process of applying for citizenship through a green card from accessing health services, or any governmental services. It shows that if you access X number of services over a certain time period, then you automatically lose your ability to apply, or are put at the bottom of the list of applying for permanent citizenship status or a green card. And this has been a very calculated campaign over the last two years, and in January, the Supreme court didn’t really help. They chose to neither support or stop the passage of that kind of action. And so, States are allowed to practice this in the selective choosing of applicants based on the Public Charge. And unfortunately what happens is misinformation disseminates down to my patients to a point where they feel that “Well, if I access any services whatsoever, I’m going to be penalized in my ability to get immigration and legal status and to do what I came here to do, which is set up a financial foundation for future generations of my family”.

And it’s the most horrible, despicable thing. It’s done under the guise of whatever political points that politicians know are needed for the next midterm or presidential elections. I can’t be blind to these things that I zoom out to because they’re a part of my daily life and my patients. As a primary care physician, I believe one of my main roles is advocating on behalf of my patients and helping them navigate, not only the complex healthcare system, but the political system that prevents them from being the healthiest versions of themselves, or getting their family the health care that they need. And so, the more that I learn about these things, and I have to learn about them and know about them to help my patients, it becomes so overwhelmingly sad to realize that the system is set up specifically to keep marginalized groups in oppressive states.

And I think that’s why I take so much inspiration from people who are not medical physicians, or who don’t have a direct medical link, but still recognize this important human need to do whatever they can, whether it’s through photography, whether it’s through telling stories, whether it’s through narrative art, of showing that everybody has a story to tell if you’ll just listen. It’s the most important, valuable thing I think you could ever say. It’s a mission that I believe in very deeply. And I think all of us would be better served if we could take a step back and listen to some of these oppressed and marginalized groups and say, well, what is it that I can actually do to help you? Even if it’s not a medical thing, how can I help improve the situation? And I think frankly, people would be surprised to see how much they can help and do good if they’re willing, willing to listen.

In terms of my own family, my parents are living in Florida now, with my younger siblings as well. My dad works in Florida and my mom’s at home as well. They were actually quite sick, with respiratory illnesses at the beginning of the onset of all of this in late March, early April, and I was quite worried. My dad has underlying health conditions. So I was very worried and I was trying from afar to coordinate what I wanted for them; go get tested here, do these things. But, though I get upset about some of the restrictions and what we’re doing in California, Florida is just the worst of the worst. So they weren’t able to get access to any quick testing. They were limited in their ability to even get tested or get support. Luckily my father has a great primary care doctor who is always willing to listen to my perspective and they’ve both recovered just fine. And I don’t actually know if they ended up having COVID or not, but luckily they’re doing wonderfully right now. Just like everybody else, they’re experiencing the social impacts of all this. My dad’s been at home from work since March. They have a granddaughter who’s two years old who lives a couple blocks away who they’ve seen only through drive by visits, and that’s something that’s affecting them. I think in every part of society, nobody’s really free of that, of those restrictions. But it takes it’s toll.

There are moments from this time I will always remember as a physician. From the very first, in late March through early April, when our clinic really shifted to limiting the number of in-person visits and doing mostly phone visits and trying to abide by as many to public health regulations as we could, we became a primary respiratory testing site for COVID. So any hospital employees that were potentially exposed, or any community members could come to our clinic and get tested, and right at the onset we saw the highest volume that could be managed in our section of Riverside County. And I remember one of the first patients that came in, I talked to on the phone, and he was having very mild symptoms; cough, cold type things, but just generally felt like he wasn’t doing too well. And I said, okay, we’ll do the swab. We swapped him on Tuesday. And at this time it was still taking three or four days for the results to come back because the technology wasn’t there yet. So I called him on Thursday afternoon with the results and his wife’s picked up and she said, “Oh, he actually went to the hospital because he wasn’t feeling too good. We obviously know that he’s positive, even though we hadn’t got the tests back, but thank you for letting me know”. And then my plan was to follow up with him on a phone visit on Monday. But then Sunday evening, because I’m listed as his primary care physician, I got an electronic message summary from his chart, from the hospital where he was, that he had died from COVID. And it was something where up until that point, I had been so aggressively reading everything I could get my hands on and trying to put into practice these public health measures, and saying, okay, we’ve got to fight this thing. But right then it really just hit home. This was somebody who, just as I’m talking to you now, with perhaps some sniffles and a little bit of shortness of breath, it just escalated so quickly. And it was devastating. I remember my nurse who actually did the swab. And I do want to say now that physicians are often lauded as the frontline workers, but I’m not the one actually physically swabbing every single patient, thousands and thousands over the last two months. That’s my nurses who do that every single day with no recognition, no kind of anything. They’re the front of the front line. I don’t consider myself a frontline worker. I am a supervising physician and in the course of the pandemic, the frontline workers are absolutely the nurses. And I remember when the nurses found out, I told them that Monday at work, and they were so devastated.

It was, for all of us, really the first time that we felt ‘this is real, this is here. This isn’t some abstract idea. This pandemic is here now’. And unfortunately, that was the beginning of a cascade of all these notifications about patients I’ve known and taken care of for a long time, that they were either being admitted to the hospital, or unfortunately dying from COVID. And again, it makes it that much more frustrating when you’re dealing with folks who still consider it abstract and not a real entity. But as angry as I get, it’s also that same pity I feel when I look at people who are texting and driving. It’s the same mentality that everybody has, ‘Well, it’s not going to affect me. So long as I’m okay and my immediate family is okay, I don’t really need to take any precautions. I trust myself.” And it’s very selfish, unfortunately, but that’s also how our society is set up. So I take comfort in folks who actively try to deconstruct that idea and do things like what you’re doing to give us a sense that, “Hey, we are actually much more connected than any of us realized.” And the sooner we act on that, the less likely these things are going to continue to plague the most vulnerable communities in horrible ways.

I touched on this in terms of my own experiences with depression, just going through the experience and having those very low points. And any doctor you speak to, I think, will be honest and frank about that. But it’s also important to highlight the uncertainty of what lies ahead. And that none of us know what our new normal is going to be, or how is this going to shake out. I’d be curious to actually know what each individual physicians or frontline workers can access to and what support on an organizational level is there for them in terms of, not just like a “Thumbs up, we’re here for you, here’s free Panera”. But like, we’re here, we’re setting up access to mental health services for all of our providers who are undergoing this right now. I’m very lucky that we have a clinical psychologist on staff at our residency program, who I have on speed dial, and she’s an amazing woman. But I’m curious, if every place that claims to support their physicians in some way, what are they actually doing to show that. What does that look like?

And I hope that you’d find that that’s an overwhelmingly positive response, but I worry sometimes that a lot of it is just show. And when I think about my friends who were doing urgent care work and living in a tent outside the garage, separate from their kids. There’s no amount of gift cards that you can do to mitigate that damage. And so it’s very scary. We’re lucky because it’s just my wife and I, but I would be lying if I said we didn’t change the trajectory of what we thought about starting a family, given what’s going on. You know, we were very deliberate about that. As a family doctor, I also deliver babies. And so the first time I delivered a mom who was wearing a mask and having a hard time, I’m looking at the monitor on the baby. And the first thing that we do when baby’s showing a little sign of distress is put the oxygen mask on mom. And as soon as I did that, everyone kind of tensed up. And it’s just such a different experience than what it should be, when the most beautiful time in any person’s life becomes this very scary situation. I have no experience or training in dealing with that, other than just trying to do what I always do, which is listen to the patient and comfort them, show confidence that I can handle this situation, but it’s harrowing.

And I don’t think that part of it is going to get better anytime soon. For as long as there continues to be this divisiveness in the general public, it only exacerbates those sentiments of dread or fear about what could lie ahead. But I’m interested as a student of history, is this our reckoning, are we going to substantially change things enough that we don’t allow this to become the new normal? Or will it be like Nine 11, where after that everyone just very passively gave up all of their personal liberties and what exists now, in terms of security access and our phones or TSA, is just the new norm. And we all just went from Tuesday to Wednesday and that was it. That’s all we know. And if you grew up after 2001, that’s the only life you know. And so I think we have an opportunity now to change that, from both a public health and a human rights perspective. Whether we do or not, it remains to be seen. But like I said, when I zoom in close enough, I’m very hopeful that there’s momentum to make that change. And that’s all I can hold onto, is that hope.

The most profound impact that is made upon you as a doctor are the patients that resonate with the mission that you identify with. And for me, that’s always identifying the parts of our most vulnerable community that are already stretched thin and are stretched even further by the pandemic. And as I started to see those patients in clinic more and more this week, what defines this moment for me wasn’t a dramatic COVID encounter, it wasn’t with somebody who had this horrible respiratory illness. But two patients I saw this week, back to back.

One was a pregnant girl who had a urinary infection that had been noted several times before at different encounters and had been prescribed antibiotics, but hadn’t seemed to be cleared. And when the resident physician who precepted the case to me was telling me about it, we were tried to understand, why is it that her infection hadn’t gone away? And we discovered that she hadn’t actually taken the antibiotics. We thought, well, that’s curious, and I was asked the resident why that was the case, but they didn’t know. And when I talked with the patient, she told me that she was waiting for her boyfriend’s next paycheck, because she thought that would be a time when she would feel comfortable spending money on something other than food, because they’re so strapped and his work is so touch and go with what’s going on with the pandemic. And as somebody who works in community health and who knows that we have the ability to give her the resources so this is no longer a problem, it was heartbreaking to know that somebody was rationing her care for something that could be disastrous for her and the baby’s health. If the infection were to progress and she had preterm labor and horrible outcomes, all the sort of things that we know could happen.

And then the very next patient I saw was a phone visit and I was telling them that their test result for COVID had come back positive. They’re a relatively young and healthy person, so it was reassuringly unlikely that something bad was going to happen. But when I asked them who do you live with, they said they had elderly parents and grandparents all living in the same home, a multigenerational home. And telling them to self-quarantine is one thing. But how do you self-quarantine away from your at-risk loved ones in one apartment room? She said, I’m responsible for getting their groceries and going out for them, what am I supposed to do? And if I’m on lockdown or self-quarantine for 10 to 14 days, what provisions do I have to make up for that? That was one of the questions that I carried with me into discussions today with our nutrition teams. But it also spoke to the larger issue of how we get so wrapped up in the death count and the case count as markers of how things are going, and really that’s such a far off and relatively abstract end point, as a metric of the pandemic. Of course it’s the one that’s the most serious. But what we miss when we do that is all of the people who are already existing on the margins of society, who are now pushed to the absolute limits and the health effects that are going to come from that, from the hidden ramifications that are in some ways, by sheer volume, much more deleterious on the level of millions. But we don’t appreciate that because we’re not thinking about those people at the forefront.

And that’s where I feel like my voice is to amplify, to show and highlight how these most vulnerable groups are at risk of the worst outcomes. And yes, death and being hospitalized and intubated is certainly one terrible visible manifestation of that. But so is not being able to get the treatments that you need or the food, or the financial stability that carries you through just normal health and the safe progression of a pregnancy or whatever else. And it’s heartbreaking to see. But I remain inspired by the level of community action that I’ve seen since the pandemic. And specifically, with this nutrition partnership that I work with through Riverside County Public Health, that has created an excellent resource for patients who identify as having food insecurity, meaning at some point they have disruption in their ability to obtain and maintain their nutrition levels.

The partnership allows for networking with other local food banks and food organizations and using grant money to coordinate and access better nutrition for these folks. And not just any nutrition, but healthy nutrition. And they actually have a program where they can get subsidized checks for farmer’s markets in the area. I was talking to the team I collaborate with because I’m their ‘champion provider’, or the physician that coordinates with the local health department for this exact purpose around food insecurity. And I was talking to them today and they were saying, “Dr. Bajwa, normally we give out anywhere from 10 to 15 checks between the two farmer’s markets in Moreno Valley and Hemet on any given week.” And today, in the morning period for their farmer’s markets, between the two of them they gave out close to 300 checks. So, on one hand, it’s sad to learn that there’s so many people who are that in need, but it’s great that we can actually connect those dots. And that I can identify people in my clinic who may utilize those services and hook them up with these programs is really uplifting.

But it requires the patients understanding that that’s available, and the community knowing that’s available, and the physicians also recognizing that need and screening for it and referring out the same as they would any other medical condition. And that’s where as an educator, my role comes in to say, okay, well, how can we better analyze and screen for these social determinants of health and then act on them? Because that to me is the most desperate part of this pandemic, and it gets lost in the fray of political talk and death count and case counts and all these other things. Because you can’t put a number on how many people are struggling to make ends meet and put food on the table, if they’re have chronic diseases and other difficulties, that may not reflect in the death count. But it’s a massive toll that we all, if we believe in this idea of community, need to be accountable for.

Physicians typically come into the profession with a tremendous sense of empathy. But it also causes us to carry so many burdens for each of our patients who are in such desperate conditions. And it makes it that much more sad and difficult to navigate when you feel like you’re by yourself. That’s why I’m such a strong proponent of physicians collectively working together with a unified voice to amplify the stories and the work that other people are doing within the community. Not just physicians, but community partners to help these most vulnerable groups, because that’s the only way we’re going to have success. It can’t be any one physician trying to battle this on their own, it’s just never going to work like that. We all have to understand what’s available and coordinate with the community partners and fight this thing together. Because we talk about vulnerable groups as if they’re another sector of society, but we are all vulnerable, right? We’re only as strong as the most vulnerable parts of our community. And if we really take that to heart, our level of action goes up exponentially and we’re much more likely to make effective, lasting change that’ll carry through way beyond to when COVID is behind us. And we’re starting to realize how we can improve the social structures that are in place to get everybody to a level where they can be the best versions of themselves. That’s idealistic to some degree, but it’s what I believe in. And that’s what I work towards. And it keeps me going every day.

Dr. Nikki Mittal

Interviewed 07.01.20

Dr. Nikki Mittal at Riverside University Health Systems specializes in pulmonary and critical care. She lives with her husband and 5 year old son. I talked to Nikki about how she handles end of life discussions when people can’t easily visit family. From her colleagues; she has a gift for handling this impossible moment with great care and respect for patients and family. Nikki and her team are also treating inmates from Chino prison and Riverside County jail’s big outbreaks.

At the beginning of the pandemic it was a lot of extra hours of planning for the hospital. I took charge of the ICU at my hospital, leading the response for COVID. How we were going to separate patients, what we were going to do when we had 12 patients, 24 patients, 50 patients? We made a flex plan up to 200 ICU patients and built teams for who would respond to all of those patients. We peaked at about 18 ICU patients. In terms of our regular ICU census, the ER was just getting COVID patients and weren’t getting a lot of regular patients. Now we are getting a lot of COVID patients, but we were also getting quite a lot of regular ICU patients. So we were really busy.

At the beginning, the discussions amongst staff were, “What is this? How do we treat it?” My USC fellowship had a weekly alumni Zoom meeting on Friday evenings. It was great to see people you automatically trust because they’ve trained under the same people as you, and to hear their experiences. Because they’re doctors who are spread out across the U S, so to hear “Oh, this is working, this is not working” was interesting. It’s gone beyond that now because I think we realized that really, not a whole lot is working or helping. Now it’s a lot more of “How long is this going to go on?” And “How do we build a hospital within a hospital where we have COVID patients separated, while we still have regular patients? And how can we open up and go back to some kind of normal care.”

Early on, it seemed if someone said something on Twitter, then that’s what everyone was trying. If someone had a random idea that maybe something might work, then we’d spend all this time thinking about it and exploring it and deciding if it was worth it. At the beginning, the rules were changing every three days. First, it was we can’t do BiPap, and then all of a sudden we can. And it was changing so fast, the information wasn’t able to get out in any official form. So if I started something that we had previously said was no longer allowed, and then we changed our minds, I didn’t get a lot of pushback from the nurses. I may get questions like, “Hey, I thought we weren’t supposed to do that”. But it wasn’t in a confrontational way. It was like, “Oh no, new data shows this is happening. We changed this, so this is why we can do it.” We all got along. It’s been good to see that we stuck together through it all.

I think we’re all a little bit worn down, we’re kind of all over it. We work together very well as a team with the nurses, the respiratory therapists and the other physicians in my group. There’s five of us, pulmonary critical care attendings, and then we have residents. I’ve been blessed in that we were already a pretty cohesive unit. I very much trust the nurses and know when they call me, that I take it seriously. They know they can come to me without worrying that I’m going lose it or blow them off. So at least walking into a pandemic like this, we already had a strong team.

I don’t think there’s been anyone now that has ever been through a situation like this, whether they’ve been a doctor for five or 30 years. Which is why I got tasked to create a plan, because I went to the head of my group, when things started really going crazy in Italy. Because Italy is a very advanced medical system, so if they’re drowning in patient deaths, that’s a very worrisome sign, because they’re not third world. A lot of our critical care research comes from Italy because they’re on top of it. And so I went to him and said, “Hey, things are going really crazy over there. Have we started planning as a hospital or anything? I’m panicking inside from what I’m reading. So I said I’m going to just take over and start planning if you don’t want to But if you don’t, I’m going to do it, I’m going to make some executive decisions without talking to you and you’re going to need to trust me because I really need to put plans in place. Otherwise I’m gonna have a nervous breakdown. I can’t handle what I’m reading and knowing it’s coming and have us just sitting here like ducks.

Not every critically ill patient can be saved. Anesthesiologist have gotten pulled to cover nights in our ICU in case we flexed out hard. And one of the old, very experienced anesthesiologists said “Let me tell you something, Nikki. An experienced surgeon will sit back and watch their patient die. A young surgeon kills their patient”. Meaning, sometimes you have to just let time take its course and don’t meddle too much. A younger doctor might say “Someone said to try this, and someone said to try that”. And I thought that’s such an important idea. If the patient is going to pass away and there’s nothing more we can do, it’s important not to push all these therapies that may do more harm than good.

I feel like people are getting sick of even wearing masks. The attitude is, fine, we’re going to return to normal, and people are going to really just disregard everything that’s happened and go back to full normal. It’s difficult at work because family members of patients trust you less when they can’t see you and meet you. Because they can’t visit, they don’t see how much work is going into the care of their family member. And I’ve had patient’s families, when I call them to give them updates, say “How come you’re not doing that”, or “You don’t want to do something else because of COVID, you’re not going to offer these things because of COVID”. But we’re still doing everything we can. We’ll obviously take COVID into account, but that’s not changing any of the basic care that we provide, whether the patient is positive or negative. We’re still doing everything that we can. But right now, family members still aren’t allowed to visit, even with COVID negative patients.

In the last week I was on ICU, it was super busy. And I had a lot of deaths. I had six people die, which is an exceedingly bad ICU week. And a few of them were actually quite young. And just calling all the family members of these patients and having to say, “Now they’re dying, you can come in. Let me call and get approval from the admin, and then you can come and visit”. It’s just so hard to have all of these conversations over the phone, as opposed to in person where they can feel that you actually have some compassion, whereas over the phone, it’s so dry.

I had some classes in Med. School on how to have these discussions and you have some simulated patients where you do it. But really, I learned through residency, by just sitting in on every single family meeting I could. I decided in my first year of residency that I wanted to do critical care, so I knew a large part of it was going to be not saving everyone. But at least I can try to ease a family member’s idea that this person is dying. Try to make that transition a little bit easier for the family. When I was an intern, every time I was in the ICU, if there was ever a family meeting going on, no matter who was running it, I would jump in. And you see a lot of really bad ways to do it. And then you see a lot of amazing ways and you kind of pick up the sprinkles. And I would give credit to the palliative care team at LA County+USC. Dr. Pamelyn Close taught me a really good baseline on how to put out that bad news and the key words to use. You should use the word suffering, it’s not unkind to say that. And you should use the word failing if something is failing. I’ve seen residents recently say things like, “His liver is not doing very well”. And I tell them, you can’t say “not doing very well” because that doesn’t have the same impact as failure. And the truth of the matter is his liver is failing. When you say an organ is failing, it really gives them a better idea of what’s going on instead of not doing very well. So they taught me the appropriate words, without being harsh but to not sugarcoat it. I think it’s just doing it over and over and over.

In terms of my personal experience, my husband got admitted with COVID. It was the worst night of my life. Luckily our son had gone to stay with my sister, but it was 2:00 AM and he was telling me he couldn’t breathe. And I was thinking this doesn’t make sense. He’s 38. I thought maybe this is a panic attack, but he’s never had panic attacks. And here it is happening right in front of my face. And I’m not recognizing it, because… I didn’t. And finally I remembered I had a pulse-ox machine and I checked his oxygen level, and it was low. So I took him to the ER but Kaiser’s ER didn’t admit him. So I brought him home for two hours and he still was not doing well. I talked to the Kaiser ER doctor who was very rude and dismissive. And so I ended up bringing him to my own hospital and he got admitted for a night there. And just watching him hover, knowing he was hypoxic and that all of the COVID patients I had taken care of were so critically ill with a low chance of survival. I literally thought about what I would do if he died and I became a single parent. He’s 38 years old, cross fit classes four times a week, very healthy, no other medical history, no other issues. And it took him so long to recover, he’s still dealing with stuff, and he got it at the beginning of March.

I just wish that people would listen and wear the masks. It’s such a strange thing to fight in the whole, grand scheme of the world right now, given all the racial injustice and the pandemic and the poverty. There have been death threats to the public officers in LA County and Orange County. I mean, all anyone’s asking is a mask, and that it would lead to death threats. I think it’s insane. I don’t know why there’s so much distrust for the medical system. I understand some parts of it, the larger systemic injustice in medicine, that not everyone gets equal access, which is why I work at a County hospital. I very much don’t mind the resource limitations to help the people who don’t have the means as much. But all these people came into my clinic today, and I had to say, “I’m not going to come into the room unless you’re wearing your mask”. And they’re asking me, “Does it really matter, do you really believe this thing is real?” And I said “I should take you upstairs and show you all the people that have died or are actively dying. And then you can ask me if I don’t believe in it. Last week I was in 20 rooms with COVID patients, breathing in some of the same air, so who knows how much exposure I’ve had. So for your own good, you should be wearing a mask, to protect yourself from me. Not even me from you.”

Annie McGuire, CORE

Interviewed 06.06.20.

Annie McGuire is an executive producer. She’s also a good friend of mine, so I wasn’t surprised she didn’t wait long before making herself useful.

I had a full work calendar traveling internationally through October 2020, and then everything just postponed until next year, or cancelled. So I spent most of March and April watching all the pain; loss of life, of human connection, feeling uncertainty about my future, and anguish about our federal “leaders” heartless negligence. I numbed myself on Netflix for a while, but one day felt I needed to help somehow. I researched COVID-19 volunteer groups and found CORE, created during the Haiti earthquake. They provided support on the ground in the Bahamas after the 2019 hurricane and continue to regroup in times of emergency.

I was assigned to the VA Center testing site in Santa Monica. The first day was an orientation for supervising testing and how important it is to give directions as clearly and gently as possible, people coming in for testing are often nervous. There are different positions on the team; directing traffic, scanning and handing people their test kits. We stand outside their car and walk them through it. Because we supervise a self-test, we don’t have doctors and nurses on site, although we have police officers and EMT’s, in case someone gets a little aggressive or agitated. One person, instead of following directions just took the test tube of solution and drank it so the EMT had to escort them to the hospital.

CORE keeps us very safe with PPE, and separation from the test subjects. We wear a long gauze cover up and an N95 mask, a regular surgical mask over that, then a space shield on top of that, and have gloves on. The work is voluntary. CORE provides us with a number of therapy sessions, in case we have anxiety or depression during this crazy time. I had my first session yesterday and I’m going to continue.

The test is free, provided by LA County. About 1,500 cars come through a day. After I took one guy’s test, he held up a sign that said, “Thank you, Hero”, with colorful hearts around it. I almost started crying. People are very grateful we’re here. It makes me feel I’m making a difference.

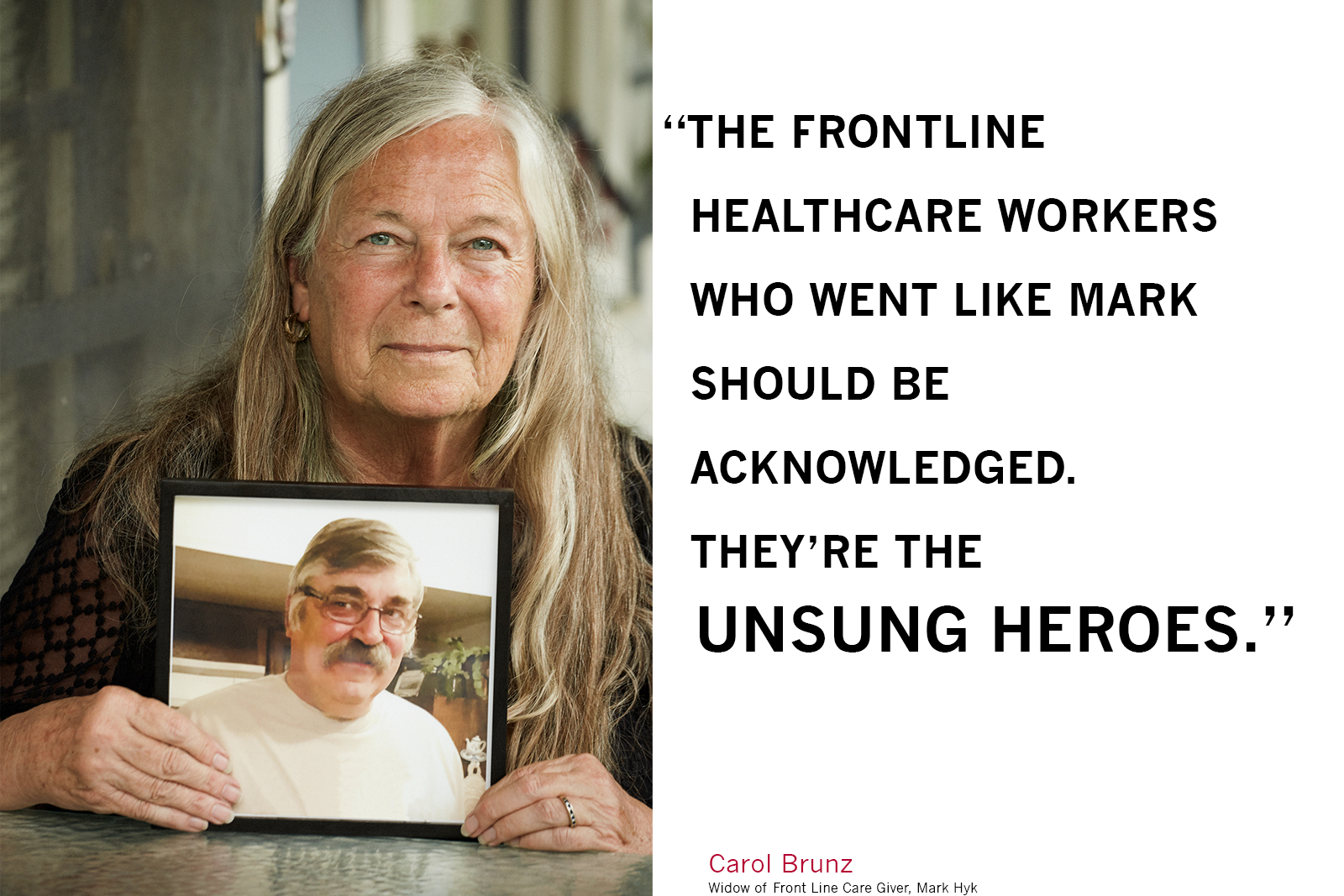

Carol Brunz

Interviewed 06.03.20

Carol Brunz’s husband of 19 years, Mark Hyk succumbed to Covid 19 on May 9th after a heroic 38 day fight. Mark was 66 years old, in great health before his illness and tirelessly energetic. A former firefighter who followed his dream of helping people into work in a rehab facility as an occupational therapist. Carol told me, Mark would often say, “I believe in the power of rehab!” The day he became unwell, that facility had its first Covid 19 death. It has since had 20 deaths and is now known to have been the center of the virus’s outbreak in San Bernadino County. I already knew from the mutual friend that had introduced us, Mark was a very beloved family man and member of his community.

Here, Carol remembers Mark, their life together, the kind of man that Mark was, and his last days. Carol alternates between speaking about Mark in the present tense, and in the past. When we met on the front porch of the lovely home on Cypress Avenue they had shared, Mark had just been gone 24 days.

We’ve been together for 19 years. It was a second marriage for both of us, it was a good second chance.

Mark was born in Rochester, New York. His parents were Ukrainian. His mother was born in the United States, but at the age of two, her family moved back to the Ukraine. His father was born in the Ukraine just before World War II. They both came to Canada, and then to the United States during the war. His father served in the military, and both his parents became naturalized citizens. So, Mark was first generation American.

He grew up in Rochester. He went to Rochester Catholic grade school and junior high. I just learned from an old friend of Mark’s that he had been accepted into a very elite high school in Rochester sponsored by the Edison company. The school was called Edison Tech and you had to be selected and go through a pretty rigorous acceptance to get in there.

He would oftentimes say “I’m a rambling wreck from Edison Tech and hell of an engineer.” The idea was for the students to get their basics, and become mechanical engineers. He graduated and because it was the time of the Vietnam War he was drafted, so he didn’t go on to school right then. He was in the army but then the war ended. He opted not to stay in when they allowed the people who had been drafted to continue service. Though he hadn’t been sent to Vietnam, his technological experience and things he’d studied in high school, meant the army had him on target for being a mechanical engineer.

But that’s not what he wanted to do. He wanted to be an occupational therapist. That was his goal. And he also wanted to be a fireman. He wanted those two because his best friend’s father was a fireman in Rochester. I’ve learned this from his friends just recently. I knew little bits and pieces of this, but now I know more about his history and how it all fits together. He had spent a lot of time as a boy with his friend’s dad.

So he went to the Fire Academy in Rochester and then decided to try going to school to become an occupational therapist. He went to school in Massachusetts to get the bachelor’s degree required to get an occupational therapy degree. And then came out here to Loma Linda, and went through Loma Linda’s occupational therapy program.

He worked at Loma Linda fire service. And then when he graduated with his Occupational Therapy, he went to work for San Bernardino County in behavioral health. OT’s have a wide variety of places where therapists can find a niche, and what he worked with there was behavioral health. One of the things that he did was start a program in the County for people who had been diagnosed as schizophrenic. He initiated that program to help them come back into society after their diagnosis. After being on medication, and going through the psychological issues of their diagnosis, they need to know “What do I do now? How do I get a job? How do I do that?” So the occupational therapy was about helping people to exist in their environment. He started the program, which was called Team House, and they would come and spend the day there and learn. There were programs to learn computers. There were programs to graduate high school, all kinds of different things they could learn.

When Arnold Schwarzenegger became the governor, they cut funds for behavioral health across the state. The County cut that program, which cut his job. After working for the County for 23 years, he was jobless for the first time. His second love working in OT was rehab. And so he went to work for acute rehab centers, nursing homes, where somebody goes if they’ve had a significant injury and need rehab. And as an occupational therapist, his role was to help that person get home, to be back out of that rehab center. That’s what an occupational therapist does. Different from a physical therapist that works on muscle. He would always say, “I believe in the power of rehab!” He would always come home sharing success stories. That was always wonderful to hear, what that person had gone through, what they had to overcome to be able to get home, start getting back to work, doing whatever needed to be done. And that showed his character. It was just who he was. He loved helping people, whether it be patients, family, or friends.

Several of us in the neighborhood here used to do really massive Halloween decorations. Around the corner, down the street, there were probably 10 houses that did this. We would have up to 4,000 trick or treaters come though. A lot of candy, but also a lot of people who remember him. And that was another way of giving back for Mark. It was his way of being able to have somebody enjoy the holidays, like he had loved them when he was a child.

On the 24th of March, Mark came home from work. We always did taco Tuesdays but that night he said, “I’m not hungry. I don’t feel well. I’m tired”. And Mark was never tired. He had an immense amount of energy and would never say I’m tired, but that night, he said “I’m really tired. I think I’m going to go to bed early.”

Quarantine was already in effect, where you’re supposed to be staying home.He was working at the Cedar Mountain Post Acute Rehabilitationnursing home in Yucaipa. The next day he had a fever and started not feeling good, and getting a cough, the day that he became ill, their first patient died.They’ve now had 18 deaths. It was the first big outbreak in this area. After that they started looking into all of this. No one knew that they had COVID until the first patient died. And then by Friday of that week there were 56 confirmed cases at that facility.

We had talked the weekend before, about what would we do if one of us got sick, you know, how would we handle being in quarantine? What would we do to take care of each other? At that stage we both felt fine, but thought we should think about it. He knew nursing homes we’re being hit all over the country, that was in the news. I’m the one that has the health issues, not Mark. He didn’t have any health issues, not high cholesterol, none of the things that you think of for somebody that’s 66. He was really healthy.

We have a cabin in Lake Arrowhead, 45 minutes away, and so he just said,

“I think we should separate if we need to. And one of us go to the cabin. We have one bathroom on the main floor that works, and you have to go through the bedroom to get to it. We can’t really quarantine if we’re having to do it here”. So the morning when he woke up with the fever, he called the doctor and said, should I come in and get tested? Because here’s where I work and here’s what’s going on. And the doctor just said, no, just stay home and see where it goes. So Mark just packed up everything and went to the mountains that day.

I was very concerned about how he would care for himself if he got sick, but it’s just not in his nature to have that discussion. He went there and the next morning his fever was high and he was having trouble breathing. It went so fast for him.

He called the hospital in Lake Arrowhead, and they had him come in, he felt like he could drive. He went in and they kept him overnight. They ran the test, and gave him oxygen and sent him home. We stayed in touch on the phone. He went back to the cabin Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and Monday. He got the test results back on Monday, that he was positive. And in the interim he had a device he put on his finger to read his oxygen levels, so he was continuously checking his oxygen level. And he called the hospital and said, do I need to come back in because my oxygen level is so far down? He shared that he’d been at the nursing home at the time of the outbreak and that he didn’t want to bring that to their hospital. It’s a small hospital, and what should he do? So they decided to send a respiratory therapist to the cabin to set him up with an oxygen machine. So he could stay home and have that machine, which is essentially a tank and a mask, which is what they would have done at the hospital. And since he knew how to use one because of his work experience, they were quite comfortable with him doing it himself.

On Monday afternoon he said, “This is just getting worse. This oxygen thing isn’t helping. It’s not enough”. And so Monday about eight o’clock, an ambulance came and picked him up at the cabin, took him to the hospital in Lake Arrowhead and then after three hours, they transferred him down to Riverside community saying that they have the best facilities, the best options for treatment over going to Loma Linda or Redlands. And a friend’s doctor said, that’s correct, it was. And Mark told me when I talked to him, after he’d gotten to Riverside, “I have the best respiratory therapist doctor in the whole region taking care me. I’m really happy to be here.”

That was Monday. On Tuesday afternoon and they had to intubate him. They had to put him on a ventilator.

Probably the hardest thing was not being able to be there with him. Three months before that, a different virus, I’d have been right there next to him holding his hand, being there with him. If they were on a ventilator having to fight, you’d be there to help them.

He was at Riverside for three weeks and then they transferred him to UCLA

because they had more options for treatment there. And their goal at that time was to take him off the ventilator and get him on to what they call a tracheotomy. He was strong enough to be able to transfer hospitals, to do that. So we had great hopes. It didn’t work.

There’s an article someone sent to me that describes the disease and what it does to your system. And it’s called a rampage through the body. And it talks about what it does, what the disease itself does. And it’s exactly what happened to Mark. It doesn’t just go to your lungs. It goes to your kidneys, it creates blood clots and so many other secondary things happen. And that’s what happened to him. He was on the ventilator for 38 days. The strength and the fight that he had…

I can’t say enough about the medical profession for trying. They gave it their all and finally it was his heart. They tried medications, they tried a proning bed, that turned him upside down, to opens up the lungs. They did all of those things. They tried a malaria medication. They tried steroids. They tried. It just wasn’t enough.

Two weeks before he passed, they called me in and told me, “Mark’s heart is really struggling. We think he’s COVID free, so we think you could come and see him”. So I got an Uber and I went to the hospital. I got to see him for an hour because they didn’t expect him to live through the night. I got there at three or four in the afternoon and I stayed until 5:30. I got back home, at nine o’clock, and he’d rallied. He wasn’t conscious because they keep them under terrific sedation for the ventilator, but he rallied. Things started kind of turning around. They were concerned about with his heart, some of the side effects of the medicines that they tried may have caused heart damage. But again, the COVID does that too.

He was getting AFib, where his heart would just race and they would have to do a shock to get it to slow. Not like shocking to jumpstart your heart again, after it had absolutely stopped, but a little shock to reset the electrical charge, so it will stop racing. And every time they would do that, his blood pressure would go down to almost nonexistent. So he was fighting this war back and forth with his heart. And again, he had no heart problems, he had a strong heart going in. So they started doing more testing then to find out why there was a heart problem, what was going on, why was this coming and going. And they discovered that he had a hole in his heart that no one previously knew about. They think that it was from the COVID, that it had caused the hole in his heart. Most of the time they would do a surgery and correct that, but they couldn’t because of the condition he was in, he was just too unwell at that stage, too fragile.

So, two weeks after that I got another call from the hospital and they said, he’s hit another really fragile point with the heart. We think that you should come and see him. So I got to go again. And I had the priest come to give Mark last sacraments. So I was able to be with him for an hour again. I had to agree to another two weeks of being quarantined after being in his hospital room. I’ve been quarantined for six weeks, which was fine. I’d do it again. Just to spend that time with him. And then his heart stopped in the middle of the night. They called me.

And I thought how much I wanted to be with him. And how unfair this diseases. I would have told him, don’t go to work. But that wasn’t in his being.

I can’t do a funeral. I can’t do a Memorial. Ten people can come, but our relatives aren’t here. Mark was cremated yesterday in Redlands, but I couldn’t be present.

So, I just prayed. It was helpful to go through the pictures you’d asked to see, it was good. If you go to a Memorial service or you went to a funeral, usually they share pictures of that person. And it was good to do that.

For now, I’m living one day at a time. I have a son that lives in Montana by Glacier National Park and a son that lives in Denver. And they both came and spent last weekend with me. They had to spend two days to get here and two days to get home, to spend three days with me. They’d previously lost their dad, when my youngest son was 18 and my oldest son was 25. Their dad had been in a car wreck and was in a coma for three months and then in a nursing home for three years, and then he passed. It took me 12 years before I remarried, until I met Mark. For my sons it was hard because Mark had become their step-dad. He was so loving with them.

My youngest son lived here in Redlands for three years, and he and his wife had a little one when they moved here who was three. Ayla just adopted Mark, they were just so close. He loved spending time with her and her baby sister. For my kids, just to give you an example, he’s been to every high school graduation of my grandkids. I have six grandkids. Four of them graduated high school in Montana. We drove to Montana. We went four times for high school graduations, two college graduations and many, many more times than that. He just adopted them and they adopted him as a grandpa.

Mark had a daughter Heather who grew up in Redlands and moved away to go to school in Idaho, and now lives in Washington. I have a lovely memory of Mark and his daughter, along with her two kids Lana and Casandra at his daughter’s wedding, and just how happy that all made him. They were all just so important to him.

I kept telling him that he’s a clone for Tom Selleck. He could have been Tom Selleck’s younger brother. Tom Selleck’s family is from Slovakia. Ukraine and Slovakia are neighbors like Kansas and Nebraska. They’re just so similar. They’re so many things. The dimples, the ears, it’s so there, you know.

I wrote something on Facebook, that he was the guy that went into burning buildings to take care of people. He’s the front line person that takes care. He was taking care of his patients when he got sick, and that’s who he was. When he was very sick, I wrote on Facebook, asking my friends to keep him in their prayers. The next week I gave an update that he was holding his own and I was sure the prayers had made a difference. We were just holding onto hope. Mark and I had a hundred year old tree that came down in our yard a year ago, on Valentine’s day, it just fell. It didn’t damage too much of the house, it just fell out into the street. We had a microburst that took three trees right up here by our house. It was windy, it was bad. After it fell, one of our neighbors asked for one of the big limbs because he did carvings and Mark gave it to him. And he came by, right after Mark went into the hospital, and he gave me a cross that he’d made out of the wood from the tree. And I held on to it, that was my prayer. I had it in my pocket. I just held onto to it, and I can’t tell you the strength that it gave me. I said to friends was, hold onto hope. This is what I was doing, I was holding onto the hope.

And we made it to 38 days with Mark on that ventilator. And I kept on praying. Someone had sent me something about the power of 40. The number 40 is mentioned 157 times in the Bible, and the power of 40 usually means a change will occur. And I kept praying for the power 40, to get there, counting every day, 37, 38. We’re almost… It’s going to change, they’re going to be able to do the trach, they’re going to be able to do this. They wanted him to get stronger so they could do the tracheotomy. It went 38 days. We just didn’t quite reach the power 40. The people who went like Mark did, there should be something, some acknowledgement. Because they’re the unsung heroes, the ones that didn’t know, and the doctors didn’t know what to do. They didn’t know how to fight it. They could guess, but they just didn’t know.

Two weeks before Mark got sick, we went on a drive around town, looking for what kind of tree we might get, to replace our fallen tree. We live on Cypress Avenue, we have Cyprus Circle on this side of our house. And so I had said, “Maybe we should find some kind of a Cypress tree”. And, we were driving around town and Mark said, “Well, the best place in town to see Cypress trees is up at the cemetery”. They’re just gorgeous, hundred year old Cyprus trees. As you drive around Cypress Circle by us, those trees in the circle are a hundred years old too, the same type of Cypress trees that are in the cemetery. But the trees in the cemetery have gotten water. Ours are kind of out in the middle of the street and they’re a little scrappier. But anyways, it’s a beautiful cemetery. He said, “Have you ever gone through the cemetery?” I said, no, I’d never driven through there. Mark had, because he’d lived here since 1976. He’d been to funerals there. So, as we were driving through, he said, “Could you see yourself being buried here?” And I said, I’ve never really thought of that. And asked him, “Have you?” And he said, “Yeah, I’ve always thought that I wanted to be buried next to my mom and dad in Rochester.” And I put my hand on his knee and I said, “I don’t care where I’m buried. I just want to be buried next to you”. End of our conversation.

So Mark has been cremated, which is new to me. Being Catholic, that’s never been an option. I’ve never been at a funeral for a family member who had been cremated. But we didn’t think we had a choice because of the COVID. And then, in talking with his daughter, she didn’t know that he had said that, about his parents. So we’ve gone through the process of looking into whether his ashes can be buried next to his mom and dad. They will bury him right next to their caskets, and they will put a Memorial there for him. He has two sisters still living and they’re both in New York, a nephew that he would have considered his son, three grandnieces and two grandnephews all in New York. So we plan to take his ashes to Rochester to do that, as part of the Memorial for him. But we can’t do that now, they wont even talk to us until after September. The cemetery won’t accept his ashes right now. They couldn’t transport them. That’s what we know as norm now, but there’s no norms in this. There’s nothing normal.

The hard part for me is, I need to talk with somebody else who has gone through this. I can talk to you, but it’s different if you’ve gone through this. So I need a support group and they can’t have support groups now because you can’t get a group of people together. So they’re trying now, because things are starting to open up, maybe in three or four weeks. But I need it today. And I needed it yesterday.

And the other thing I’m finding for myself is I can’t go out. I can’t bring myself to leave my house. I talked to my neighbor Melissa who is a doctor about it. I said, “Is this like a PTSD?” I can’t get in my car. I can drive, but I tried to go to the bank yesterday and it didn’t work. I’m finding that I can’t go anywhere right now.

Anyway, thank you for letting me talk about Mark.

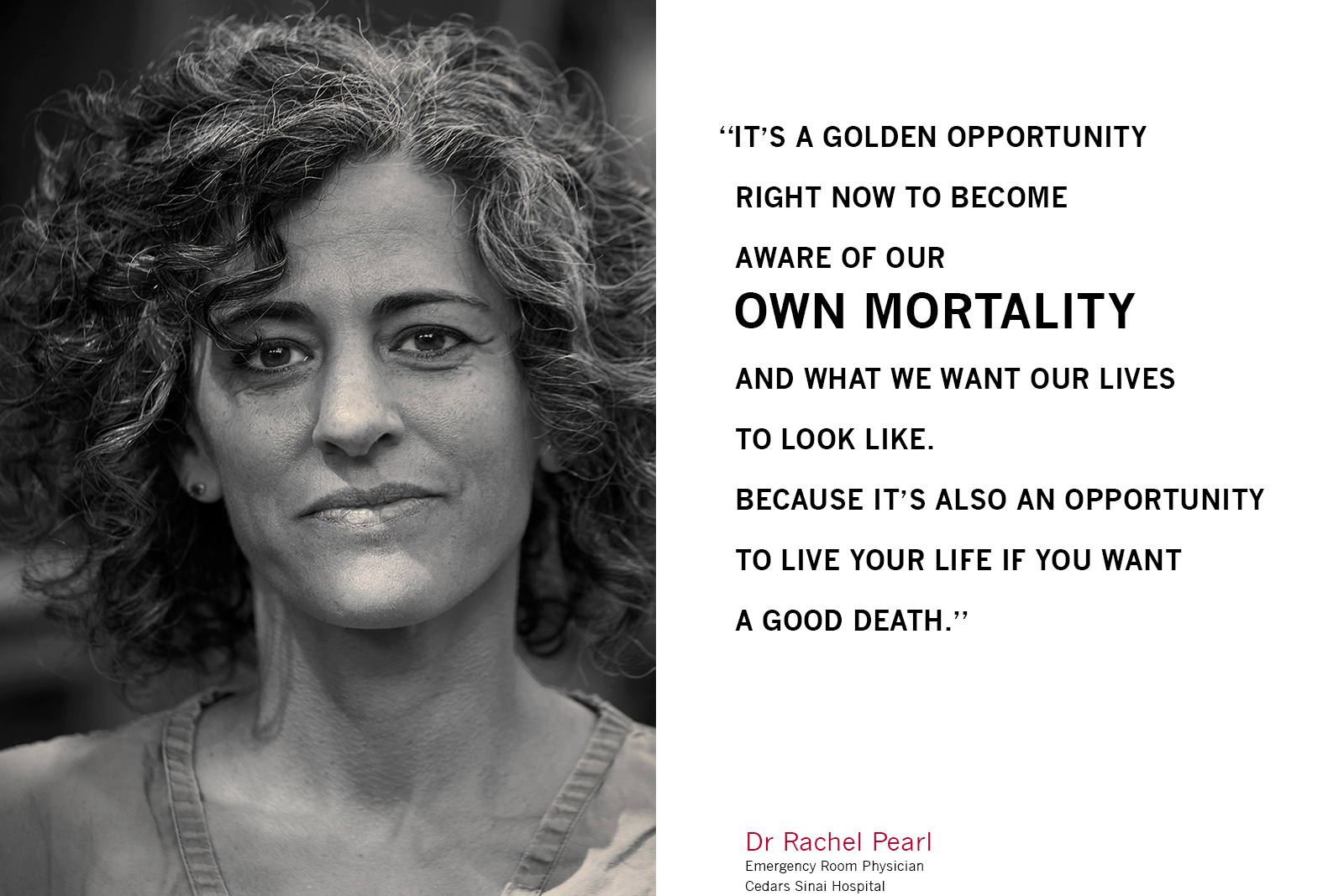

Dr. Rachel Pearl

Interviewed 05.19.20

Dr. Rachel Pearl is an emergency physician at Cedar Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, practicing for 20 years. She lives with her writer husband, Chris and their three sons. Harry’s nearly 14, Isaac nearly 12, and Levi, soon to be 8. Everybody’s birthday is in the next month or so, a full house and a lot of festivity coming up.

In Rachel’s own words:

My experience as an emergency physician has evolved. At the very beginning of the pandemic, in mid-March, I became ill myself. And so right as we started to take off into all the adjustments, in patient flow, patient care, with heightening anxiety and so forth, that’s when I got sick. I was a patient under an investigation basically, I was suspected to have COVID. I was never tested because there wasn’t sufficient testing available at my facility. In the beginning, it was a bit chaotic, we had testing available through the LA department of public health, but only with very strict criteria. You had to meet those criteria in order to get a test, and it wasn’t easy. It took a while for our facility to develop it’s own tests. So, right when I got sick, the testing guidelines strengthened and it became a little more strict.

And so, I wasn’t eligible, even as a health care worker. In order to qualify, I would’ve needed to have been sick enough to be admitted to hospital as a patient. In some ways it made sense because the accuracy of the test wasn’t a hundred percent. So even if you have a negative test, that didn’t mean you don’t have it. And the recommendations for care were the same, regardless of whether you tested positive or not; to stay at home until you’re well and asymptomatic. Whereas if you’re going to be admitted into the hospital, it is really important to segregate patients with and without COVID. So it really makes a difference if you’re testing positive or not. So I just tried to respect those guidelines. That’s what I was telling my patients. I suspect that I could have gone out and found a test somehow, but I didn’t think it was really going to make a difference. I didn’t do it.

I was sick for a good three to four weeks. Not terribly ill, just a sick enough to not interact with others. I was on isolation within my own house for two weeks. We’re fortunate that we have enough space in our house with the way it’s configured. My eldest son was also sick at the same time, so I was isolating in my room and he was isolating in his room, and everybody else was in the main space. It worked out fine, and it gave me the opportunity to kind of get my arms around this thing, to dig in, be a support to my colleagues, and learn about the disease. To fortify my own approach.

Frankly it was terrifying at times. Because right before I got sick, I took care of very sick people and I knew what that looked like. I knew that the disease didn’t manifest in it’s worst state until a good week into your symptoms. So those first six or seven days where you’re just waiting to see what’s going to happen, there was a lot of anxiety, a lot of insomnia, a lot of meditation, and just kind of working through thoughts about mortality.

Right before I got sick, when we were having department meetings about what our approach would be, what we would do with the department, the flow and so forth, I had expressed some concern about the mental health of our staff. I had heard a lot of things coming out of Italy. New York wasn’t quite on fire yet, but those Italian doctors were quite traumatized and I was concerned about our own staff. So I immediately became appointed in charge of mental health. So that time that I was sick, I wasn’t so sick that I was bedridden, I was able to spend a lot of time researching ways to support the staff. I had a little committee, and we came up with a lot of resources for staff. At the same time, my husband was creating a charity with some friends called Dine 11, in order to get funds donated to restaurants, who in turn made meals for front line health care workers.

My friend, comedian Rob Cordry, reached out to see what I needed, and so we decided we needed some humor in the department. So he and all of his comedian friends came up with a bunch of personalized, humorous videos with thanks to the doctors and nurses of our staff. So that turned into a whole fundraising project for PPE, for staff all over the country. So that was nice to become a part of. I was very busy. I wasn’t doing medical stuff, but trying to find ways to stay active and help people and keep positive and so forth. I wasn’t feeling that bad. And because our lifestyle is quite frenetic normally; I work a lot, I don’t sleep very much, the kids are really active, they have a lot of sports, this was downtime. It was very nourishing.

Then, since I got back to work and we’ve flattened the curve, it’s been okay. I was ready and geared up to go back and see the worst, and then I entered a department that was kind of at a standstill. We’re seeing about half of the normal numbers of patients that we’d previously seen on a daily basis, pre-COVID, and we were subsequently running with a skeletal crew. Usually it’s very frenetic in the emergency department and you’re just burning the candle at every end and going full speed. So this was unusual. Compared to normal life in the ED, it’s been more restful.

Of the patients that are coming in, we’re still seeing plenty of COVID patients, and those patients can be quite ill. And in general, the patients coming in are quite ill, and we’re seeing a lot of psych patients. It’s a funny blend right now. The numbers are coming back up, as we’ve loosened restrictions and people get a little tired of waiting things out, they’re coming in. We’re doing more elective surgeries again, and doctors are referring their patients to get admitted for urgent workups, so things are really picking up again now.

We are seeing COVID numbers declining. They’re still trickling in. A little bit of ebb and flow. For instance, we had a homeless patient with psychiatric illness who was seen by one of my colleagues the other day. He came in with leg pain. He hung out in the department all day, sobering up while we tried to figure out what to do with him. He ended up leaving against medical advice because he came to and felt okay. And he went out and got drunk, fell and hit his head, immediately came back, I intubated him with a head injury and he was positive for COVID. So this was somebody that had been in our department all day long, with no signs of COVID. Thankfully we have protocols when we intubate a patient and the staff was fully protected, because that’s a high risk, aerosolizing procedure that can spread the virus all over the room and all over the department. But no one could have guessed that he was ill with COVID. And so there’s these tricky ones kind of hiding under rocks. There’s a lot still happening.

In the scientific community, there’s a lot of respect for the scientific process and understanding things with scientific rigor. So I think right now, most of us just respect the fact that we don’t know a lot. There’s a lot we don’t know, that we don’t understand. Is this disease something that people can build immunity towards? We don’t know. We just saw somebody who tested positive in March, negative in April and was back in the hospital in May, positive. So I think there’s just deep respect for what we don’t know. We want to loosen things up as much as anybody else. But, mostly we’re just afraid that if we loosen the restrictions too quickly, we’re going to get slammed. We’re worried for our own health. We’re worried for people and the resources that might not be available if a tidal wave comes the way that it hit New York.